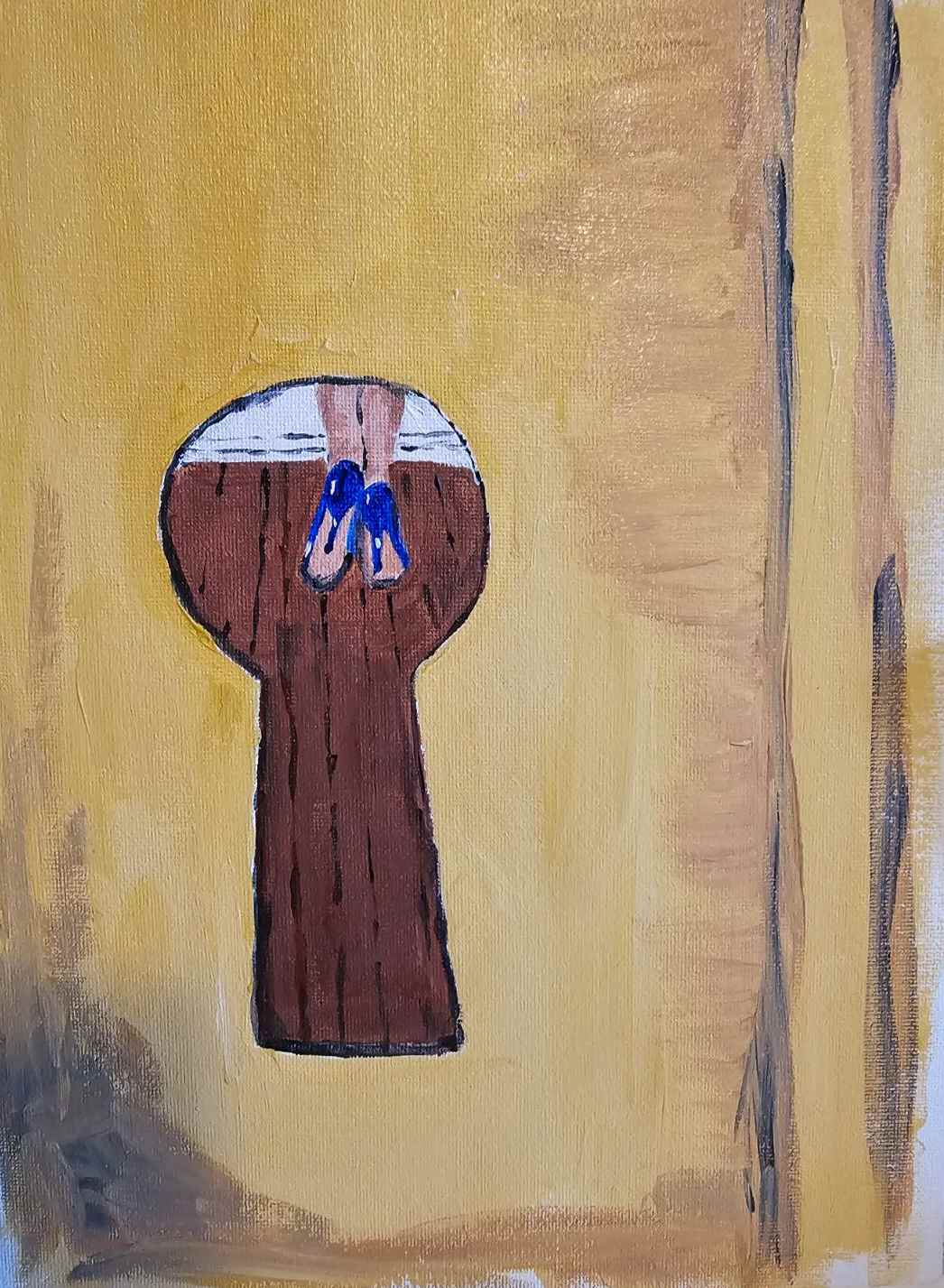

| ECHOES |

|

PHOTO CREDIT: by wal_172619,

https://pixabay.com/photos/columns-pillared-hall-stone-8171283/

Gini’s mother left when she

was 12 years old, not a good time for a young woman, a girl

really, to lose her mother. Not there really ever is a good

time. But Gini was rushing through the highs and lows of her

first real crush, a boy who sat across the aisle from her all

afternoon, and without a mother to talk to she had only her

friend Alicia to rely upon for advice. What to do, when to do

it, if she should do it or anything else at all.

Her mother had known all that

stuff. Mothers do.

It wasn’t exactly a surprise.

Her mother and father had been fighting steadily for a couple of

months, yelling and screaming, followed by the loudest silence

on the planet.

She was in bed. The yelling

had stopped, finally. But too quickly. Gini sat up in bed and

tried to listen to the sudden quiet. She followed her father’s

footsteps out of the bedroom and across the hall and into the

kitchen, then a noise in their bedroom. It might have been doors

or drawers opening and closing.

She thought of those TV shows

and movies where some character puts a glass to the wall and

listens to what’s going on on the other side of the wall and

wondered if it actually worked and wished she’d thought about it

and brought a glass to bed with her.

Gini heard her mother flick

off bedroom lights. Then her heels echoing on the hallway floor,

the long, long hallway floor. It sounded heavier or something,

somehow, than the sound her heels usually made on the striped

wood, the echo betraying her progress down the hall and to the

table by the door and the rattling of her car keys, the door

opening, then shutting.

“Renée is gone, I’m sorry to

say,” her father said in the morning, pouring her a bowl of

Cheerios and handing them to her. “And I don’t know when or if

she might be coming back.”

He reached to the counter and

got the carton of milk and handed it to her.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

He’d never called her mother

by her first name before, and he never again called her anything

else.

Years passed. She relied on

girlfriends, the occasional mother of some boyfriend who’d

always wanted a daughter, teachers and counselors and college

professors – all of them supplying her with the guidance her

mother should have and her father couldn’t. Or wouldn’t. Because just as she’d lost her mother that night, he’d lost his wife. She would go on with her life, he would wait for his to be over.

She often thinks of her mother, Renée, still angry that she’d

walked away, especially when she leaves her office and walks

across campus to teach, walking through a concrete passageway

between buildings, the click of her heels echoing her progress. From Julia Berger: CLICK THE PLAY BUTTON

From Milly Mahoney-Dell'Aquila:

|

HOME

FLASH O'DAY STORIES

MY BOOKS ODDS 'N ENDS |