| IN HARMONY |

|

Soon,

many angry men would arrive, and there was still so much to be

done. It was not unusual, and Gelila thought it was happening

far too often. She and Dejen had worked many hours at their

jobs, and they had lived modestly and saved their money, and

they were the first of the families to purchase their own house.

It was not much. Three small

bedrooms and one bathroom and another the Americans called a

half bath. But it was more than they had ever had.

But then it became the meeting

place for all of her countrymen, and Gelila began to long for

the days in the low-income apartments where they were treated

like cattle but at least had a place to themselves.

“Where is your mind, Gelila?”

Kelemi barked. “The teff sits too long.”

“It has not been too long,

Mother. It has been four days now, and I have stirred it twice

this morning.”

“Then you stir too much.”

Genzebe went and stood between

her mother and her grandmother and looked into the large pot

with the fermenting teff, breathing in its musky, sour

smell.

“You like to argue,” she said,

looking from one to the other.

“Men argue,” her grandmother

said, laughing. “Women discuss.”

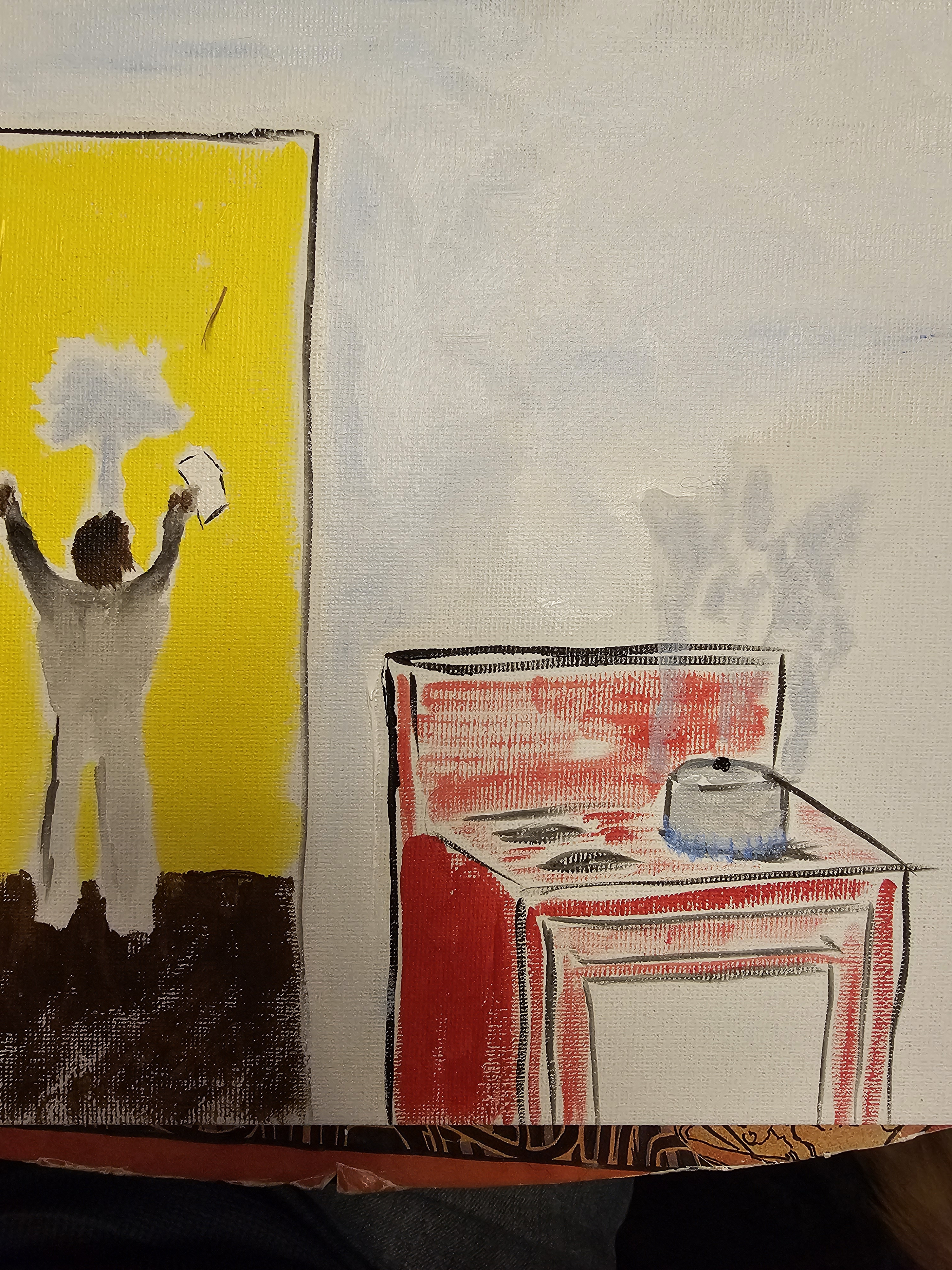

Soon they would begin the

assembly-line-like cooking of the injera, the gray,

spongy bread all of the other dishes would be eaten with.

The men had taken over

Gelila’s new home the week before to form their Issues

Committee, where they had drawn up a list of grievances they

planned to take to management at the beef-packing plant where

they all worked. They were men, she thought, brave and bold in

the living room and sheep on the killing floor.

She knew. She worked next to

them, as did so many of the other wives.

The men filled her living room

and spilled into the hallway, speaking loudly and waving their

arms in the air, while she, Kelemi, and Genzebe hurried to

refill their plates.

They would strike. They would

march in the streets. They would form a union just for

Ethiopians.

But they would not threaten to

leave. No one wanted to go back.

“Americans have a good word,”

Genzebe said. She and her mother and grandmother were cleaning

up after the men. Kelemi scraped and stacked the dishes, Gelila

scrubbed them in hot and bleachy water, and Genzebe dried.

“Americans have many good

words,” Kelemi said in Amharic, sarcastically. She did not like

Americans but loved America.

“What is the good word,

Genzebe?” Gelila asked.

“Blowhard.

It is men talking big about the many things they will do,

pretending to have power and strength they do not have.”

“Funny word,” Kelemi said,

bending over backwards and arching her back.

“Think of a whale blowing

water out of the top of its head.” Later, the three women sat quietly at the table over cups of tea and cold injera and smiled to one another. From Milly Mahoney-Dell'Aquila:

From Angelo Dell'Aquila:

|

HOME

FLASH O'DAY STORIES

MY BOOKS ODDS 'N ENDS |